The DJs We’ve Lost: A Tribute to Dance Music’s Departed Pioneers

Posted on November 11, 2025

(An op-ed by DJ Lynnwood)

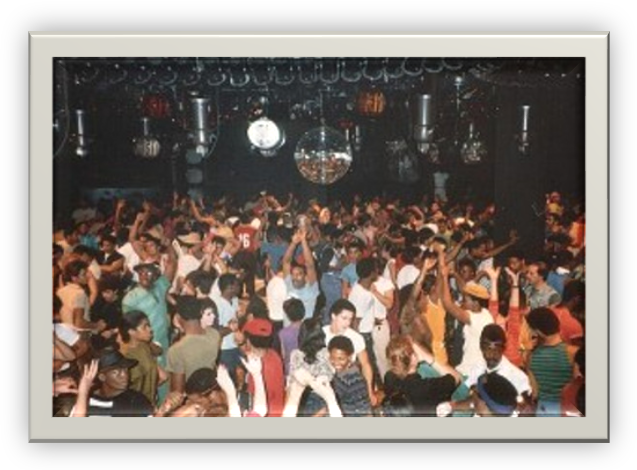

November 14, 2025 – Los Angeles CA: Before dance music became a multi-billion-dollar global industry filling stadiums and dominating festivals, it was born in cramped New York lofts, sweaty Chicago warehouses, and Detroit basements—places where records became rituals and DJs became architects of escapism. In Harlem ballrooms during the late 1960s, pioneering DJs discovered that two turntables and a mixer could create something more powerful than any single song: continuous rhythm that made bodies move and communities form. At Paradise Garage during the early 1980s, a mostly queer crowd of Black and Latino dancers found sanctuary on Saturday nights, their emotional release inseparable from Larry Levan’s wizardry. In the Bronx and Brooklyn, Latin Freestyle DJs mixed electro beats with Latin rhythms for communities navigating between cultures, creating a sound that filled the gap between disco’s death and house music’s rise. Meanwhile in Chicago, Frankie Knuckles at the Warehouse was blending disco with drum machines in sets that would literally name a genre, while down the street at the Music Box, Ron Hardy pushed those experiments even further into acid house’s psychedelic future.

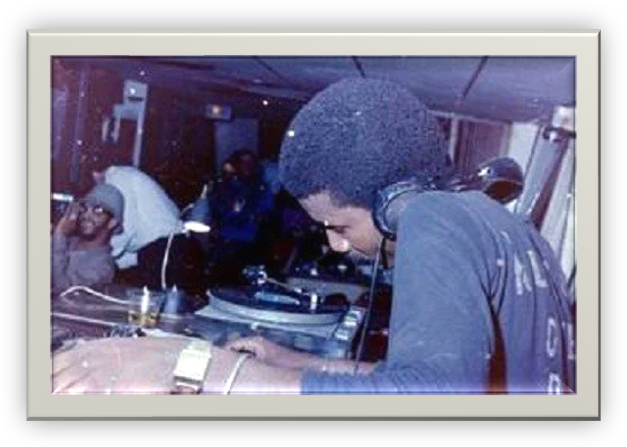

The DJs profiled here built these genres from scratch, often with little more than passion, technical ingenuity, and an intuitive understanding of what their crowds needed. They spent countless hours digging through crates, and learned to read rooms like psychologists read patients. Many died without receiving the recognition they deserved, their names unknown outside the scenes they helped create. Others achieved fame but were taken too soon—by the AIDS epidemic in the 1980s and 90s, by the substance abuse and mental health crises that continues to plague artists, by accidents and illness that remind us how fragile life is.

Their deaths represent more than personal tragedies. They mark the loss of irreplaceable knowledge: the manual mixing techniques perfected before sync buttons, the deep musical literacy built through years of live curation, the ability to create transcendent experiences through pure selection and timing. As the dance music industry grows more commercialized and technology handles what hands and ears once did, the gap between today’s DJ culture and its roots widens.

This is their story—and a reminder of what we risk losing if we forget where dance music came from.

Harlem: Where DJ Culture Began

Before disco became a global phenomenon, Harlem’s DJs were developing the techniques that would define modern dance music. They weren’t just playing records—they were curating experiences, reading rooms, and building communities through sound. These pioneers worked in an era before DJ fame, when the craft meant serving the dance floor above all else.

Grandmaster Flowers emerged from Brooklyn in the late 1960s and became one of disco’s true architects. Playing venues like the Annexe and Smalls Paradise, moving between James Brown, Marvin Gaye, and the Temptations without breaking the groove. His technical innovations—using two turntables, manipulating EQ, extending breaks—became standard DJ practice. Kool Herc and Afrika Bambaataa both acknowledged his influence on their approaches to mixing. When he passed in 1992, he left behind a blueprint that both disco and hip-hop had built upon, though his name remained unknown outside DJ circles. “Flowers was involved in the hip-hop and funk scene and had a ‘formative influence’ on hip-hop DJs such as Grandmaster Flash and Afrika Bambaataa.” (Hard Knock Radio, 2023)

Pete “DJ” Jones carried that tradition forward, running mobile sound systems that powered block parties at venues like the Hotel Diplomat and the Renaissance Ballroom through the 1970s. His technical precision impressed a young Grandmaster Flash, who learned cueing and beatmatching basics by watching Jones work. In a 2005 interview with Davey D, Jones described his philosophy: play what the room needs. For mixed-age crowds in Harlem, that meant soulful disco that kept everyone moving. He represented the mobile DJ era that made dance music accessible beyond expensive clubs, bringing the culture directly to neighborhoods. When he died in 2014 at 69, he took with him decades of knowledge about reading diverse crowds and adapting in real time.

DJ June Bug bridged disco to hip-hop’s emergence in the early 1980s. At Harlem World and venues across the Bronx, he mixed disco hits with funk breaks, creating sets that energized entire rooms. His style appeared in the 1984 film Beat Street, capturing how Harlem’s DJs blended genres instinctively. He played block parties and clubs with equal skill, understanding that the DJ’s job was to maintain energy without relying on spectacle. His murder in 1983 at just 27 cut short a career that was helping define how disco’s techniques would evolve into early rap culture. “One of the best blending DJ’s the game has ever seen.” (Rock The Bells Facebook, 2022)

These Harlem pioneers established principles that rippled through every scene that followed: technical skill matters, reading the crowd is essential, and seamless mixing creates transcendent experiences. Their deaths left gaps in the oral history of how DJ culture actually developed—the subtle choices, the technical innovations, the community-building strategies that can’t be fully captured in recordings.

New York: From Private Lofts to Legendary Clubs

As disco exploded in the 1970s, New York’s downtown scene transformed DJing from a technical craft into an art form. These DJs didn’t just play records—they created sonic journeys and pushed the boundaries of what dance music could be.

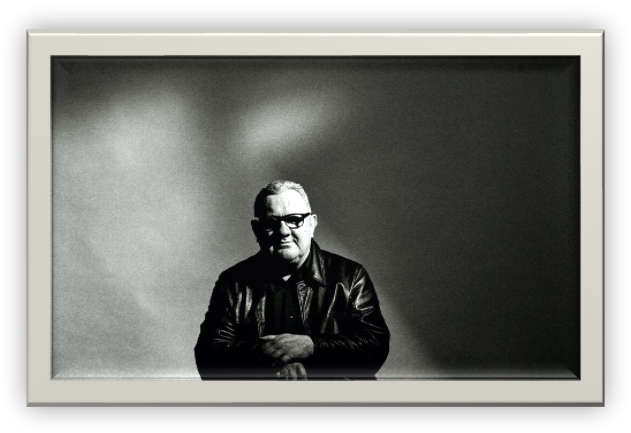

David Mancuso started it all with The Loft in 1970, hosting private rent parties in his Broadway apartment that became legendary. His approach was radical: no alcohol, no velvet rope, just impeccable sound systems and carefully curated music for a diverse crowd. Mancuso treated sound as sacred, investing in high end equipment and programming sets that flowed like emotional narratives. Tim Lawrence’s book Love Saves the Day called it a social experiment that proved dance music could build genuine community. When Mancuso died in 2016 at 72, he left behind an ethos—quality over commercialism, inclusivity over exclusivity—that underground house music still aspires to. “There Would Be No Rave, No Festival, No EDM Without Him.” (Tommie Sunshine, Billboard, 2016)”

Larry Levan took those principles to Paradise Garage, where his Saturday night sets from 1977 to 1987 became the stuff of legend. Levan treated the DJ booth like a laboratory, using the club’s custom Richard Long sound system to remix tracks on the fly, layering in drum machines and effects. He’d play Grace Jones’ “My Jamaican Guy” or Sister Sledge’s “Lost in Music” as multi-part epics that built over hours. The crowd responded to his intuitive understanding of emotional pacing. Grace Jones later said he “shaped rooms with records,” while Frankie Knuckles noted that Levan “played the space itself.” His style defined garage house as vocal, deep, and focused on connection. When he died November 8, 1992, at 38 from heart failure caused by endocarditis, the scene lost not just a DJ but a visionary who understood dance music’s spiritual potential. “LARRY LEVAN is the Greatest DJ Of All Time.” (Arthur Baker, YouTube, 2010)

The AIDS crisis devastated New York’s DJ community. Richie Kaczor, Studio 54’s resident DJ from its 1977 opening, died from AIDS in 1993 at 40. He was the steady hand behind the club’s chaos, programming Gloria Gaynor’s “I Will Survive” and Chic’s “Le Freak” with surgical precision for celebrity-packed dance floors. Billboard called him a key tastemaker whose seamless mixing influenced how remixes would function in house music. “Richie Kaczor was the DJ behind Studio 54… they never say Richie Kaczor.” (Nicky Siano, The Vinyl Factory, 2017). Jim Burgess passed that same year at 39, also from AIDS. With formal training in opera and classical music, Burgess brought compositional structure to disco at clubs like Infinity, 12 West, and through his influential Salsoul remixes. Tom Savarese praised his control and restraint, noted by Rolling Stone, making him essential to disco’s evolution into more sophisticated house productions.

Tony Smith curated Studio 54 sets alongside Kaczor, mixing disco with deeper grooves that hinted at house music’s future. After the club era, he kept those influences alive through SiriusXM shows, bridging mainstream and underground sensibilities. His death in 2021 ended a generation that remembered when disco and house weren’t separate genres but existed on a continuum of dance music.

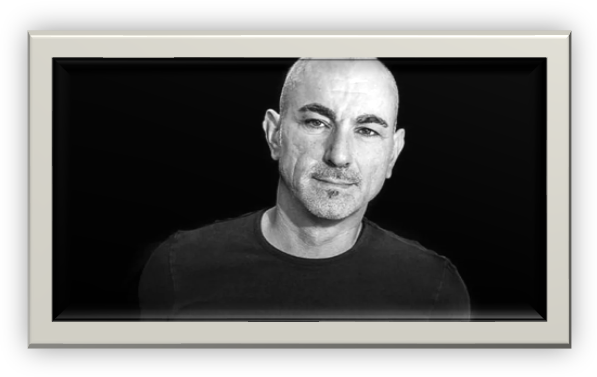

Peter Rauhofer brought European precision to New York’s LGBTQ circuit party scene, becoming one of dance music’s most respected remixers. The Austrian-born producer moved to New York in 1995 after establishing himself in Vienna, where he’d worked at record stores and as international A&R director for GIG Records. His Club 69 productions like “Let Me Be Your Underwear” (1992) initially made his name, but his real impact came through transforming pop hits into tribal house epics. His remixes deconstructed tracks into 10-minute journeys—his work on Cher’s “Believe” earned him a Grammy Award in 2000 for Best Remixer of the Year, while his reworkings of Madonna’s “Impressive Instant,” “Nothing Really Matters,” and multiple other tracks became definitive club versions. He remixed everyone from Whitney Houston to Pet Shop Boys to Mariah Carey, proving that pop material could be rebuilt into underground credibility. From 1999 until the club’s closure in 2007, Rauhofer held a legendary residency at the Roxy, where his Saturday night sets drew massive crowds and occasional surprise appearances from Madonna herself. After Roxy closed, he launched his WORK! party series at venues like Stereo nightclub, maintaining his position as a pillar of gay dance culture. His Star 69 record label released tracks that defined tribal house’s peak era, including productions by Suzanne Palmer and Celeda. On the circuit party scene—White Party Palm Springs, Winter Party Miami, Black Party NYC—his marathon sets were ritualistic experiences that blurred music and communion. His death from a brain tumor on May 7, 2013, at 48, came just weeks after his diagnosis shocked the community. The circuit scene lost not just a technically brilliant DJ but an architect of dance floor culture whose remixes remain anthems at Pride events worldwide. “His heart will always be in New York City.” (Angelo Russo, manager’s statement, 2013).

These New York DJs established that technical mastery should serve emotional truth, that communities deserved spaces designed for their joy, and that dance floors could be sanctuaries. Their losses—many to AIDS at the height of their powers—erased institutional knowledge about creating inclusive spaces and programming sets that built emotional arcs over entire nights.

Chicago: Building a Genre from Warehouse Grit

Chicago’s house music emerged from necessity. When disco died commercially, dancers needed their own spaces, and DJs created them in warehouses and underground clubs. What developed wasn’t just a new sound but a new culture, built on experimentation, community, and raw creative energy.

Frankie Knuckles gave house music its name. His residency at the Warehouse from 1977 to 1982 drew large crowds who came for marathon sets where Knuckles seamlessly blended disco, European synth-pop, and early drum machines. Tracks like “Your Love” (1987) became anthems for outsiders finding community on dance floors. NPR quoted him describing his mission: creating soundtracks for people society marginalized. After the Warehouse, he moved to the Power Plant, hosted radio shows on WBMX, and remixed major artists including Michael Jackson, winning Grammy awards that brought house music to mainstream audiences. His death on March 31, 2014, at 59 from complications related to type 2 diabetes prompted Chicago to rename a street in his honor. He’d proven that underground dance music could achieve both artistic integrity and global influence. “Frankie Knuckles, known as the Godfather of House music… a pioneer of house music.” (BBC News, 2014)

Ron Hardy took house music’s raw potential even further. At the Music Box from 1982 to 1987, Hardy’s sets were legendary for their intensity and innovation. He used tape edits and primitive drum machines to transform disco records into acid house’s psychedelic sound—his manipulations of tracks like Phuture’s “Acid Tracks” helped define the subgenre. Where Knuckles was smooth, Hardy was chaotic and bold. Frankie Knuckles and other peers considered him house music’s wild genius, with Resident Advisor later calling him the genre’s raw pioneer. His death on March 2, 1992, at 33 or 34 from AIDS-related illness robbed house of its most fearless experimenter. “Ron Hardy was one of the pioneers of house music in the 1980s.” (Ron Hardy’s radical style, waxpoetics.com)

The next generation pushed house into new territories. DJ Rashad emerged in the 2000s as juke and footwork’s ambassador to the world. His Hyperdub albums like Double Cup (2013) mixed Chicago house with breakneck 160 BPM footwork rhythms, creating something entirely new. He played Pitchfork Music Festival and toured globally, bringing Chicago’s street-level innovation to international audiences. The Guardian noted how his death from a drug overdose in 2014 at 34 devastated a scene he’d worked to elevate beyond its local origins. “Rashad was a kind soul that left an indelible mark on the music world as the torchbearer of Footwork and Juke.” (Wes Harden, Complex, 2014)

Paul Johnson survived a 1987 shooting that left him paralyzed from the chest down, then spent decades producing some of Chicago house’s most joyous tracks. His Dance Mania releases like “Get Get Down” kept the genre’s upbeat spirit alive through the 1990s and 2000s. Daft Punk sampled his work, recognizing his contribution to house’s global spread. Billboard noted his determination when he died from COVID complications in 2021 at 50—he’d never let his injury stop him from making people dance. “Today we have lost a great legend of our world house community.” (RP Boo, Guardian, 2021)

DJ Deeon defined ghetto house’s direct, explicit style on Dance Mania with tracks like “Freak Mode” that stripped house down to raw, functional elements for warehouse parties. Mixmag called him a godfather of the sound that influenced UK bass music and grime. His death in 2023 at 56 took one of house’s most uncompromising voices. “There will never be another DJ Deeon… You will be missed but never forgotten!!!” (DJ Mag, 2023)”

DJ Funk (Charles Chambers) coined “ghetto house” as a distinct style, producing raw, sample-heavy tracks like “Run U.K.” that were designed for underground parties but found audiences worldwide. First Floor described him as a Chicago staple whose energy spread to international scenes. He died from cancer on March 4, 2025, at 54, having spent his career proving that Chicago’s most underground sounds could resonate globally.

Ron Carroll added vocal soul to Chicago house. A singer and DJ who collaborated with producers like Bob Sinclar and Louie Vega, his tracks blended classic house with contemporary production. His death from a heart attack on September 21, 2025, at 54 (or 57—sources vary on his birth year) came as he was still actively touring and making music. “Very sad to hear about the passing of the incredibly talented Ron Carroll. RIP to a legend.” (Bad Boy Bill Facebook)

Chicago’s house scene demonstrated that marginalized communities could create entirely new genres when given space and freedom. These DJs built house from the ground up, often in the face of poverty, violence, and discrimination. Their deaths leave questions about techniques, philosophies, and community-building strategies that were rarely documented outside the culture itself.

Detroit: Techno in the Machine

While Chicago birthed house, Detroit created techno—electronic music that was futuristic yet deeply soulful, reflecting both the city’s industrial decline and its communities’ resilience. Detroit’s DJs and producers proved that machines could express profound humanity.

Mike Huckaby embodied Detroit techno’s educational mission. Beyond his productions on labels like Deep Transportation (including the acclaimed My Life with the Wave), he taught at Youthville Detroit, passing his knowledge of synthesis and sound design to younger generations. He worked at Record Time, Detroit’s key record shop, connecting the city’s musical past to its future. Juan Atkins praised his depth and precision in production. When COVID-19 took him in 2020 at 54, Detroit lost not just a talented artist but a crucial link between techno’s pioneering generation and its inheritors. “Mike Huckaby was an incredible talent and a beautiful soul. A giant of a man, deeply loved by all who knew him.” (Pitchfork, 2020)

K-Hand (Kelli Hand) fought for recognition in techno’s male-dominated landscape. Known as the “First Lady of Techno,” she ran Acacia Records and built a substantial European following with releases like “Think About It.” Red Bull Music Academy highlighted her persistence in demanding space for women in the genre. Her death in 2021 at 56 left Detroit techno without one of its most important voices for gender equity in electronic music. “If you look, you’ll see her name and influence all over this music. Gone too soon, R.I.P. Kelli Hand always treated me with kindness.” (Legacy.com, 2021)

Detroit’s techno legacy shows that electronic music could be both forward-looking and deeply connected to urban musical traditions. These artists took affordable gear and turned it into statements about resilience, innovation, and the future. Their losses mean fewer firsthand accounts of Detroit’s specific approach to electronic music—the soul they found in drum machines and synthesizers.

Beyond Borders: Dance Music Became Global

Dance music’s core genres spread worldwide, creating everything from UK drum and bass to European trance to experimental electronic music as DJs across continents took house, techno, and disco as starting points and made them their own.

UK Bass Evolution: Jungle, Drum and Bass, and Hard House

Britain’s rave culture spawned multiple genres that accelerated and darkened dance music’s possibilities. Kemistry (Valerie Olukemi A Olusanya) co-founded Metalheadz Records with Goldie and Storm, helping drum and bass evolve from jungle’s ragga roots into something more sophisticated. She DJed on pirate station Touchdown FM and released the acclaimed DJ-Kicks mix album. The Guardian called her a trailblazer for women in drum and bass when she died in a car accident in 1999 at 35. Her loss came just as drum and bass was gaining international recognition, robbing the scene of a creative voice at her peak. “That was the most difficult part for me. Getting over the guilt of not being able to save her.” (DJ Storm, Guardian, 2019)

Tony De Vit built London’s hard house scene from Trade, the legendary Sunday morning gay club where he held a decade-long residency starting in 1990. His relentless, hard-edged style—pushing house to 150+ BPM with aggressive basslines and epic builds—created a sound that dominated UK gay clubs through the 1990s. Fatboy Slim called him “the DJ’s DJ” in Mixmag, noting his technical precision and crowd connection. His death from HIV-related illness in 1998 at 40 devastated UK dance music. A blue plaque in London recognizes his cultural impact—acknowledgment that gay club culture deserved to be memorialized alongside other musical movements.

Trance’s Euphoric Rise

Trance emerged in Germany in the early 1990s, combining techno’s structures with euphoric melodies and epic builds. Mark Spoon (Markus Löffel) helped define the sound as half of Jam & Spoon, whose 1993 hit “Right in the Night (Fall in Love with Music)” featuring Plavka became a global anthem. The duo were fixtures at Berlin’s Love Parade, playing to over a million people annually through the mid-1990s. They also produced as Tokyo Ghetto Pussy and Storm, exploring harder techno territories. When Spoon died from a heart attack on January 11, 2006, at 39, Die Zeit obituaries recognized him as a key figure in German electronic music. Love Parade that year featured tributes to his contribution to trance’s golden era.

Robert Miles (Roberto Concina) brought trance to pop audiences with “Children” (1995), a dream house track with a haunting piano melody that sold millions worldwide and topped charts across Europe. The track’s success at Brit Awardsand beyond proved electronic music could achieve mainstream acceptance without compromising its essence. He later ran Open Lab radio in Ibiza, using his platform to support emerging artists. His death from cancer in 2017 at 47 signaled the loss of an artist who’d bridged underground credibility and commercial success. “Sad to hear Robert Miles passing. RIP thanks for the music.” (Pete Tong, Sky News, 2017)

Tomcraft (Thomas Brückner) represented Germany’s next trance generation. As resident DJ at Munich’s KW Das Heizkraftwerk from the late 1990s until 2003, he developed a following that made him a festival staple. His 2003 track “Loneliness” topped UK charts and became a global club anthem, embodying trance’s emotional directness. He performed at Love Parade for crowds exceeding 1.3 million, released four albums, and founded Craft Music label to support new talent. When he died on July 15, 2024, at 49, German electronic music lost a figure who’d remained committed to trance even as EDM shifted toward other sounds.

Electronic Music’s Experimental Edge

Some DJs refused categorization, pushing electronic music into stranger territories. Andrew Weatherall started as a DJ at London’s Shoom club in acid house’s late-1980s explosion, but his real impact came through production and remixing. His transformation of Primal Scream’s “Loaded” (1990) into an acid house anthem essentially created the album Screamadelica, which won the first Mercury Prize. The Chemical Brothers called him an “alchemist” in The Guardian, noting how he could take rock, dub, techno, and disco and forge something entirely new. His eclectic DJ sets spanned decades and genres, rejecting purism for creative collisions. When he died from a pulmonary embolism in 2020 at 56, electronic music lost one of its most fearless sonic explorers. “He said: “The worst thing anyone can say is they don’t like it. If the words mean something, get them out.”” (David Holmes, Guardian, 2020)

SOPHIE (Sophie Xeon) deconstructed pop and electronic music itself with a producer’s approach that felt like no one else. Her 2018 album Oil of Every Pearl’s Un-Insides garnered Grammy nominations and Pitchfork acclaim for its avant-garde vision—hyperreal sounds that were simultaneously synthetic and emotional. She produced for Charli XCX, helping birth hyperpop as a genre, and her death in an accident in 2021 at 34 shocked the music world. She’d opened doors for trans visibility in electronic music while creating some of the most forward-thinking productions of the 2010s. “RIP SOPHIE. A huge loss. Thank you for the creations you left us with in this world.” (Kelly Lee Owens, Independent, 2021)

Dave Ball, while best known as half of Soft Cell, had deep roots in dance music that predated synth-pop stardom. He DJed Northern Soul nights across UK clubs, bringing his crate-digging sensibility to Soft Cell’s electronic productions. After “Tainted Love” (1981) became a global hit, he continued exploring electronic music through The Grid, his acid house/techno duo with Richard Norris that produced the 1994 hit “Swamp Thing.” Ball’s extensive remix and production work influenced generations of electronic artists. When he died peacefully on October 16, 2025, at 66, Marc Almond’sstatement recalled their partnership as transformative. Ball proved that pop success needn’t mean abandoning underground electronic music’s experimental spirit. “Thank you Dave for being an immense part of my life and for the music you gave me.” (Marc Almond, Facebook, 2025)

The Ibiza Sound and Global House

José Padilla defined Balearic house through his decades-long residency at Café del Mar in Ibiza. His sunset DJ sets—ambient, downtempo, emotionally evocative—became synonymous with the island’s chill-out culture. Multiple compilation albums spread his aesthetic globally, influencing how people understood ambient music’s role on dance floors. Resident Advisor praised his ability to create atmosphere through restraint. His death from cancer in 2020 at 64 closed a chapter on Ibiza’s original generation.

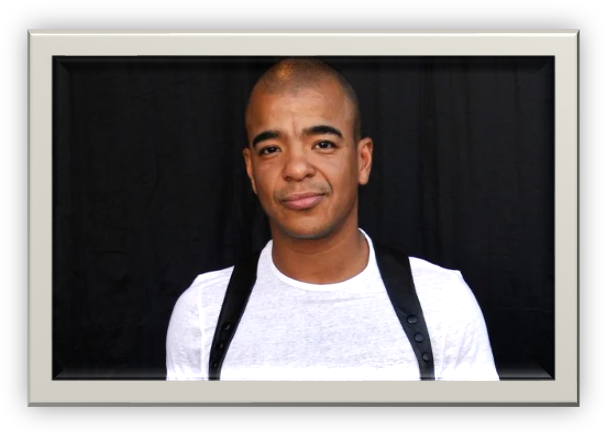

Erick Morillo represented house music’s global superstar era. His 1993 hit “I Like to Move It” (as Reel 2 Real) became ubiquitous, but his real influence came through his legendary nine-year residency at Pacha Ibiza and his founding of Subliminal Records in 1997. At his peak, Morillo played 30 gigs per month worldwide and signed a $1 million contract at Pure nightclub in Las Vegas. His Subliminal Sessions at New York’s Cielo and residencies at Ministry of Sound in London made him one of house’s most commercially successful DJs. His death from ketamine toxicity in 2020 at 49 was complicated by serious legal issues in his final years, casting a shadow over his musical legacy. Billboard noted both his contributions to house and the controversies that defined his later life. “Erick Morillo, may you Rest In Peace. One of the best djs I’ve ever seen. You inspired me so much …” (David Guetta, Facebook, 2020)

Angel Moraes took a different path, staying true to underground house while achieving global respect. A Brooklyn native who came up in Paradise Garage’s era, he co-founded Montreal’s legendary STEREO club in 1998, creating a space for 24-hour house music marathons. His label Hot ‘N’ Spycy and tracks like “Welcome to the Factory” became tribal house anthems. He remixed Pet Shop Boys, k.d. lang, and countless underground artists, maintaining credibility across decades. When he died on February 27, 2021, online forums filled with tributes to his soulful mixing and dedication to house music’s spiritual core.

Mashups and the Rise of EDM

DJ AM (Adam Goldstein) pioneered celebrity DJ culture and mashup artistry in the 2000s. His technical skills were genuine—he could beatmatch anything and create seamless blends that felt like new tracks. His residencies commanded seven figures, including a $1 million annual contract at Pure in Caesars Palace. He performed with Travis Barker at MTV VMAs, mixing rock, hip-hop, and electronic music for mainstream audiences. After surviving a 2008 plane crash that killed four people, he struggled with addiction, documented in his MTV show “Gone Too Far.” His death from a drug overdose in 2009 at 36 shocked the music world. Rolling Stone covered both his sobriety struggles and his role in making DJ culture mainstream. Eminem referenced him in lyrics, recognizing his influence on a generation. “I miss your contagious, guttural laugh and your hugs. The best hugs. Miss you every day…” (Mandy Moore, Billboard, 2019)

Avicii (Tim Bergling) became one of EDM’s biggest stars during the genre’s explosive mainstream breakthrough in the early 2010s. His tracks “Levels” (2011) and “Wake Me Up” (2013) blended progressive house with pop, country, and folk in ways that reached massive global audiences. His touring schedule was punishing—over 300 shows per year at his peak—and he struggled publicly with mental health and substance abuse. When he took his own life in 2018 at 28 in Muscat, Oman, it forced the industry to reckon with how it burned out young artists. His family founded the Tim Bergling Foundation to support mental health initiatives, and artists like Arty released tribute tracks. His death became a turning point in conversations about artist wellbeing in electronic music. “Devastating news about Avicii, a beautiful soul, passionate and extremely talented with so much more to do. My heart goes out to his family. God bless you Tim x.” (Calvin Harris, 2018)

Underground Techno in the Shadows

Silent Servant (Juan Mendez) worked in techno’s darkest corners, creating hypnotic, industrial-influenced sets in Los Angeles lofts and warehouses. His productions and graphic design work helped define underground techno’s aesthetic in the 2010s. Resident Advisor tributes highlighted how he remained committed to techno’s challenging edges when the genre was fragmenting into countless subgenres. His death in 2024 at 46 removed a crucial voice in American techno.

i_o (Garrett Falls Lockhart) represented techno’s younger generation, releasing EPs like ACID 444 on Mau5trap and collaborating with Grimes. His death from cardiac arrhythmia in 2020 at just 30 shocked the scene. Dancing Astronautrecognized him as rising talent whose potential was just becoming clear. “Going to miss you my dude, it was a real pleasure working with you and watching you succeed… may you find rest, and let your music live on into eternity.” (deadmau5, Facebook, 2020)

Continental Europe: French Touch and Italian Club Culture

France and Italy developed their own electronic music identities in the 1990s and 2000s, with Paris and Rome becoming hubs for distinctive sounds that blended house, techno, and local influences.

DJ Mehdi (Mehdi Favéris-Essadi) was central to Ed Banger Records’ rise in the mid-2000s. His productions fused hip-hop’s swagger with French electro’s sheen—tracks like “I Am Somebody” featuring Chromeo became dancefloor anthems. As part of Club 75 collective, he helped shape Paris’s electronic scene while remixing everyone from Daft Punk to Justice. His DJ sets effortlessly moved between genres, reflecting his deep knowledge of both American rap and European electronic music. His death in a tragic accident on September 13, 2011, at 34—when a Plexiglas floor collapsed at his birthday party—shocked the global electronic community. Busy P and the Ed Banger family mourned the loss of an artist who’d proven that electronic music could be both intellectually ambitious and physically euphoric.

Philippe Zdar (Philippe Cerboneschi) helped invent French Touch as half of Cassius and through his work with Motorbass. The duo’s hit “1999” captured millennial optimism with its filtered disco samples and driving bassline. But Zdar’s influence extended far beyond his own productions—he won a Grammy for producing Phoenix’s Wolfgang Amadeus Phoenix (2009) and worked with Kanye West, Beastie Boys, Hot Chip, and countless others. His production style emphasized warmth and groove, making electronic music feel human even when heavily processed. He continued performing with Cassius, releasing their final album Dreems in 2019. His death from an accidental fall in Paris on June 19, 2019, at 52 robbed electronic music of one of its most tasteful and versatile producers. “So f***ng sad to learn about Philippe Zdar last night.” (Mark Ronson, Independent, 2019)

Claudio Coccoluto built Italy’s house and techno scene over four decades. After founding Rome’s Goa Club in 1991, he became synonymous with Italian electronic music culture. His Ultrabeat party series drew international DJs and helped establish Rome as a credible stop on the global circuit. He was the first European DJ to play New York’s legendary Sound Factory, bringing European sensibilities to American house music’s birthplace. Beyond DJing, he ran The Dub label, hosted radio shows, and mentored younger Italian producers. His death in 2021 at 58 after illness concluded an era for Italian club culture—he’d witnessed and shaped electronic music’s entire evolution from disco through contemporary techno.

Recent Losses and the Scene’s Living Memory

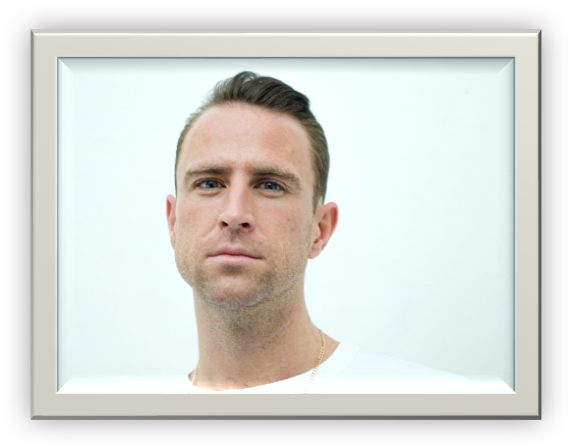

Jackmaster (Jack Revill) co-founded Glasgow’s Numbers label and became one of house and techno’s most respected selectors, known for sets that could move seamlessly between decades and subgenres. His death from complications of an accidental head injury in Ibiza on October 12, 2024, at 38 sent shockwaves through the global scene. His family’s statement noted the sudden, tragic nature of his loss—a reminder that dance music loses not just veterans but artists still in their creative prime.

These global contributors proved that dance music’s core principles—community, innovation, emotional connection—could translate across any cultural context. Their losses represent not just individual talents but entire approaches to electronic music that risk being forgotten as the scene becomes more commercialized and homogenized.

Other Talent We’ve Lost

Dance music’s reach extended to every corner of the globe, creating local scenes with their own pioneers. While their stories remain less documented in mainstream sources, these DJs made crucial contributions to their regional communities:

DJ Randall (died July 2024, age 54) was a drum and bass staple who helped push jungle’s evolution through UK raves and his production work, influencing countless DJs in the breakbeat hardcore and jungle scenes.

Mr. Bubble (Dennis Lowe, died November 3, 2021) was a pioneer of Los Angeles’s underground industrial, alternative, and early house scene in the 1990s. An original member of Club Metro Riverside’s DJ collective, he helped define Southern California’s rave culture through his innovative mixing and music production. He left behind his wife Brittanie and son Ethan, who was 11 at the time of his sudden passing.

Ame (Eamon Downes, died July 2025, age 57) co-founded the group Liquid and helped define breakbeat hardcore with tracks like “Sweet Harmony” that captured UK rave culture’s euphoric peak in the early 1990s. He fought brain cancer for five years before passing.

JD Twitch (Keith McIvor, died September 2025, age 57) was half of Optimo, running eclectic Glasgow club nights that refused to stick to one genre, instead celebrating electronic music’s full diversity across decades and styles.

Matt Tolfrey (died October 2025, age 44) founded Leftroom Records and became a respected house and techno producer, collaborating with artists like Damian Lazarus. Tributes highlighted his warmth and dedication to underground sounds.

Reda Briki (found dead June 2025, age 52) co-founded New York’s Love that Fever party and contributed to the city’s electronic music underground, though his sudden death on a boat in NYC left many questions about his final days.

DJ Ajax (Adrian Thomas, died 2013, age 41) ran Sydney’s Bang Gang label and helped shape Australia’s electroclash scene, bringing punk energy to dance music in ways that influenced the country’s electronic underground.

These artists remind us that dance music’s history isn’t limited to superclub residents or chart-topping producers. Every city, every underground party, every local scene had its pioneers who made the music matter to their communities.

The Costs: What Took Them and What It Means

The patterns in these deaths tell uncomfortable truths about dance music culture and society’s failures. The AIDS epidemic in the 1980s and 90s devastated the scene, taking Hardy, Kaczor, Burgess, and De Vit at their creative peaks. These weren’t just individual tragedies—they erased institutional knowledge about programming, technical innovation, and community-building that would have shaped subsequent generations.

Substance abuse and overdoses claimed Rashad, Morillo, and DJ AM, pointing to the pressures of constant touring, performance expectations, and a culture that often celebrated excess. Mental health crises led to Avicii and i_o’s deaths, forcing overdue conversations about how the industry treats young artists. Cancer ended the lives of DJ Funk, Padilla, and Miles. Violence took June Bug. COVID-19 killed Mike Huckaby and Paul Johnson. Accidents claimed Kemistry, SOPHIE, and Jackmaster in moments that highlighted how suddenly the scene can lose vital voices.

These deaths reflected systemic problems in how the music industry operates and how society treats its artists. As these pioneers died, so did firsthand knowledge of manual mixing techniques, deep crate-digging practices, and the ability to read and respond to rooms without technological assistance. The craft of creating emotional journeys over entire nights, of building communities through programming, of maintaining underground credibility while achieving broader impact—all of this risks being lost as memories fade.

Why Their Legacy Matters Now

These DJs left marks that define contemporary dance music, whether today’s producers realize it or not. Samples, production techniques, approaches to programming, and philosophies about what dance floors can be all trace back to these pioneers. The Tim Bergling Foundation works on mental health initiatives because of Avicii. Memorial plaques for Tony De Vit and others ensure their contributions remain visible. Chicago’s street renaming for Frankie Knuckles acknowledges house music’s cultural importance.

But the foundation they built faces real threats. As dance music globalizes and commercializes, the connection to its roots—Black innovation in Harlem, queer spaces in New York, Chicago’s house grit, Detroit’s techno vision—becomes more tenuous. Many headline DJs today prioritize playing their own productions over curation, which makes sense for building personal brands but narrows the diversity that pioneers like Mancuso and Knuckles championed. The deep record knowledge needed for truly cohesive, varied performances takes years to develop, and many contemporary DJs lack those libraries, sticking to familiar material rather than breaking new sounds.

Technology shifts the craft as well. Premixed sets synchronized to visuals and auto-beatmatching tools handle transitions that earlier generations executed by ear and skill. These tools aren’t inherently bad, but they create distance from the manual craft that defined early dance music. The question being asked more and more: does this tech reliance dilute the art, turning performances into polished productions rather than responsive, improvised experiences?

The spontaneous edge that made dance music vital—the moment when a DJ reads the room perfectly and drops exactly the right unexpected track—becomes rarer in an era of planned sets and algorithmic suggestions. As memories of the lost DJs dim—those who spent hours digging vinyl, who adapted on the fly, who understood dance floors as conversations rather than performances—the scene risks losing what made it transformative.

What You Can Do

Honoring these departed pioneers requires more than remembrance—it demands action.

Listen and Learn: Seek out these DJs’ original mixes and sets. Platforms like YouTube, Mixcloud, and SoundCloud host countless recordings that showcase their artistry. Listen to Larry Levan’s Paradise Garage sets, Frankie Knuckles’ WBMX radio shows, Ron Hardy’s Music Box recordings. Hear the difference between planned sets and spontaneous curation.

Support Mental Health: The Tim Bergling Foundation works to prevent mental illness and suicide in the music industry. Similar organizations worldwide address the touring industry’s toll on artists. Your donations and advocacy can help prevent future tragedies.

Preserve Local History: Document your local scene before it’s too late. Interview veteran DJs, digitize flyers and mixtapes, attend events honoring pioneers. Many cities have lost irreplaceable archives because no one thought to preserve them.

Attend Underground Events: Support promoters and DJs who prioritize curation over self-promotion, who book diverse lineups, who create events for real dance music culture. Vote with your money and attendance for the values these pioneers embodied.

Learn the Craft: If you DJ or aspire to, learn beatmatching by ear before relying on sync. Dig for records outside algorithmic recommendations. Study how the greats built sets that told stories rather than showcased brands.

Share Their Stories: Talk about these pioneers with younger generations who may not know the history. Share articles like this one. Push back when the industry forgets where it came from.

Dance music’s future depends on whether we remember and honor its past. These DJs gave us the gift of community, liberation, and transcendence through sound. The least we can do is ensure their contributions—and the values they represented—survive them.

They, and so many DJs still with us today, built something profound. Their innovations in technology, their proof that marginalized groups could create globally influential culture—these achievements matter. Remembering them means committing to the values they embodied: technical excellence in service of emotional truth, curation over self-promotion, community-building over profit maximization, and the understanding that dance floors can be sites of liberation and transformation.

The challenge for contemporary dance music is to honor that legacy while moving forward—to embrace new technology without losing manual skills, to achieve commercial success without abandoning underground values, to go global without forgetting the specific communities and struggles that birthed the culture. These DJs showed what’s possible when talented people create spaces for their communities. Their deaths remind us how fragile that knowledge is and how much work remains to ensure their contributions aren’t forgotten in the rush toward dance music’s next commercial frontier.

DJ Lynnwood is an internationally recognized DJ, Producer and Radio Personality. @djlynnwood